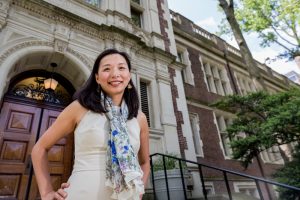

As a physician-scientist and a research team leader Alice Chen-Plotkin finds herself at home in numerous overlapping worlds.

As a physician-scientist and a research team leader Alice Chen-Plotkin finds herself at home in numerous overlapping worlds.

For many diseases and disorders nowadays, there are plenty of association studies—that is, evidence of some relation between a portion of the genome and a physiological trait. Figuring out exactly how the two are related, however, poses more of a challenge. It’s the rare research team that has the opportunity, skills, and sheer doggedness to uncover every point along the line connecting a genetic variant to the presence or absence of a specific protein in cells, and from there to the development of a particular physical condition.

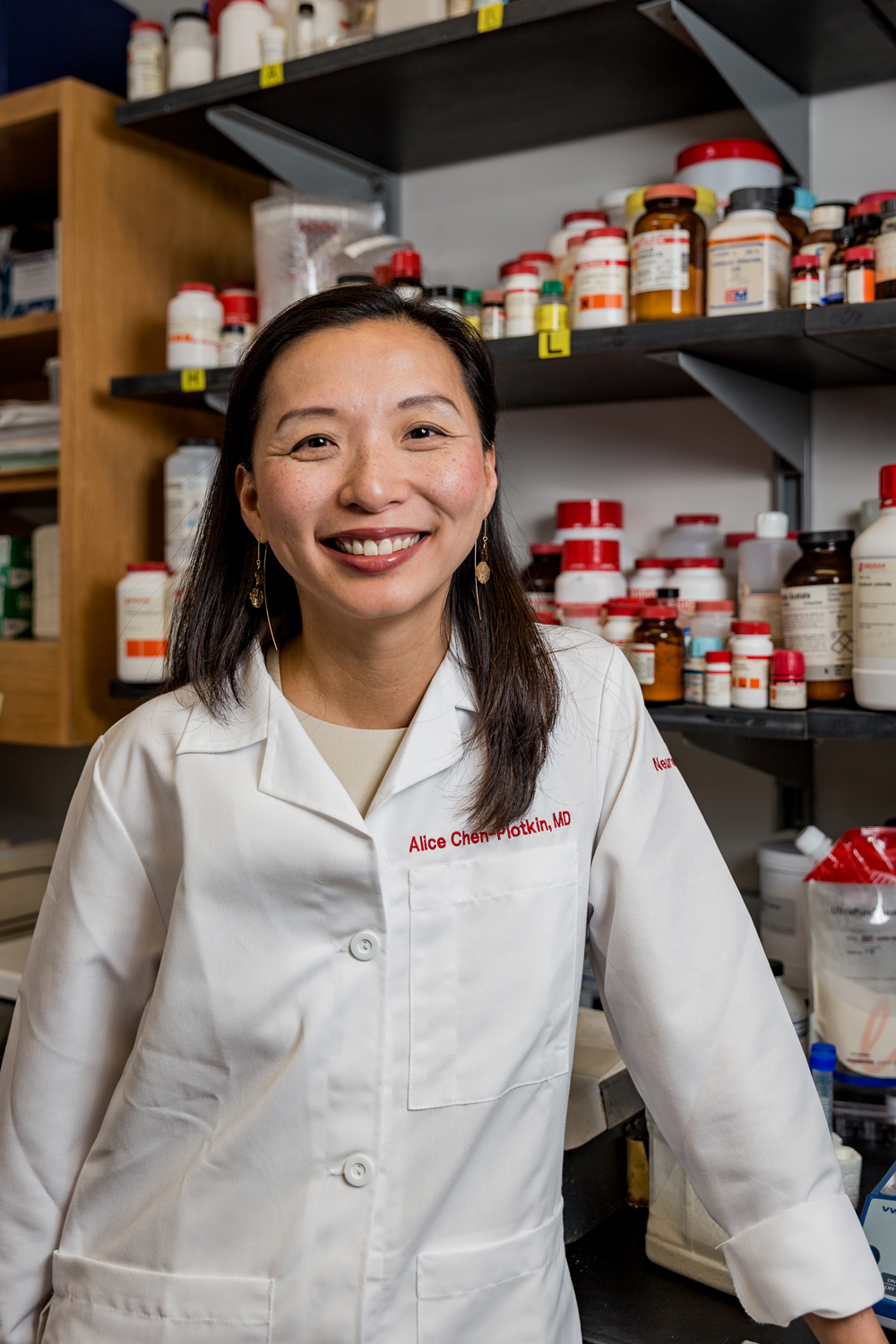

Alice Chen-Plotkin, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, knows all about the challenges of this type of investigation because she has navigated them herself. Leading a research team at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, she recently published a paper in the American Journal of Human Genetics that traces an entire chain of events leading from gene-based risk to problems with the functioning of certain cells, including brain cells, in an illness called frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). “We identified the genetic risk factor, a gene known as TMEM106B, some time ago—in 2010—and then we spent literally the next six years trying to figure out what it did,” she says.

According to the account the researchers painstakingly pieced together, certain genetic variations in TMEM106B can cause the gene to produce its protein at relatively high levels, which then interfere with the functioning of subunits in the cell called lysosomes. Since the lysosomes carry out essential tasks such as breaking down waste material and removing it from cells, anything that hinders their work can cause serious health problems. In FTLD the result is a form of dementia, with a progressive decline in language, decision-making, and/or social behavior that leaves the patient more and more dependent on caretakers and ultimately leads to death, usually within about eight to twelve years of its onset. In the United States, the disease affects between 50,000 and 60,000 people.

Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, FTLD generally spares the patient’s memory. Nevertheless, because it occurs most often among men and women in their 50s or early 60s, it can take a heavy toll both on family life and on the ability to work. At present, there is no effective treatment, but the new understanding of the disease laid out by Dr. Chen-Plotkin and her collaborators may well enable researchers to identify some promising targets for drug development.

Follow-through studies like the one published on FTLD are notoriously hard to plan because researchers don’t know at the outset which gene(s) will be highlighted by the data in an association study. They can’t predict what kinds of specialized equipment or investigative techniques they will need, or even where to look for collaborators several years down the road. The experience combines elements of a treasure hunt with those of an obstacle course—or, from Dr. Chen-Plotkin’s point of view, “It was really fun, and it was really hard work.”

Early Career Award

Back in 2008, when she received a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Dr. Chen-Plotkin was a postdoctoral fellow with no clear idea of how to use this largesse. She certainly didn’t know that her “Rainy Day/Big Idea/See-What-Happens Fund,” as she affectionately calls it, would last almost ten years and pave the way for groundbreaking research on a debilitating brain disease.

During that decade, Dr. Chen-Plotkin set up a lab at the University of Pennsylvania whose team more than doubled in size and launched a translational research program in Parkinson’s Disease biomarkers. All the while, though, her work remained grounded in clinical experience, from the medical residency that sparked her curiosity about neurological disorders to her ongoing practice of treating Parkinson’s Disease patients.

Dr. Chen-Plotkin credits the Career Award for Medical Scientists grant with giving her the means to persevere during years of follow-through study, but some credit is due as well to her abiding intellectual curiosity. “In a job like mine, you do it because it’s a passion,” she says; in fact, “it can all too easily creep into other areas of life and just take over.” Fortunately, everyone in her household shares the same passion. Her husband, Joshua Plotkin, is an eminent scientist in his own right (and a recipient of BWF awards in both 2001 and 2005), applying mathematics to the study of evolution. Thus it seems quite natural that, as Dr. Chen-Plotkin explains, “We’ve always been very porous in letting our work life mix in with our home life. For instance, we live within walking distance of the lab, and our kids (ages 10 and 5) are in and out of there all the time. They know everyone in the lab—it’s almost like an extended family.”

However porous her work/life boundaries may be, Dr. Chen-Plotkin makes a point of keeping a couple of hours clear every evening just for her family. “I want it to be something that everyone can count on,” she says. “But also, as a physician-scientist-parent, I’m all these things all the time. I don’t think that when I’m parenting I’m not being a neuroscientist—I’m thinking about that all the time—and likewise, when I’m at work I can still function as a parent. I think people sometimes feel they have to hide their personal lives from their work lives, and it seems to me that would be a mistake. I want to show people who may be concerned about being a doctor and a scientist that you can do those things and have a family too. I hope that in the future, someone worrying about this will say, ‘I remember when I had to practice my conference talk for Alice and her baby was sitting there,’ and see that it was perfectly fine.”

Also competing for a share of Dr. Chen-Plotkin’s time is her medical practice: she continues to set aside time every two weeks to see patients, mostly those with Parkinson’s disease, whom she has followed for a long time. This work is so rewarding, she says, partly because of the way it feeds the motivation for her other pursuits. “I keep the clinical practice both because I like it and because I think it gives me an added perspective that I wouldn’t get from doing research exclusively,” she says. “It reminds me every now and then to say, ‘What are the chances that this thing, this line of investigation I’m focusing on now, is ever going to help anybody, as opposed to being science for science’s sake?’ Of course, we need people doing basic science too, but when you have real patients coming in regularly for treatment, it brings home the purpose of your work in a different way. Also, understanding the world outside the little circle of your lab gives you some perspective.”

The circle of people who work with her represents the larger world as well because their roots lie in so many different countries. Dr. Chen-Plotkin didn’t consciously set out to make her lab an international place; she simply tried to find the best people who wanted to work with her. During the election season of 2016, however, she found herself thinking a great deal about questions of immigration and national origin. When she came to draw up a list of where all her co-workers had come from, she says, “I was very interested in the fact that even many of the people in my lab who aren’t themselves immigrants have immigrant parents. I like that a lot, because in some ways that is the dream of science writ large. It could be the undergraduate in the lab, it could be a grad student or the principal investigator, but the dream of science—the best ideas combined with the patience and the will to work them through—that could come from anyone. Here you get the world’s talent wanting the opportunity.

“One thing that’s great about science,” she goes on, “is that it brings together people who, left isolated on their own, may have part of a great idea but not the whole thing, or may have some amazing concept but not the means to work it through. But among all the people in a lab, when things are going really well, everybody’s consumed with the work at hand and almost losing themselves in it, almost like a flow state. And I think that’s really important to understand, that there are these commonalities that can exist among people from anywhere in the world and from very different backgrounds.”

In a gratifying return to the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Dr. Chen-Plotkin now serves on the advisory committee of the Physician-Scientist Institutional Program. She knows very well how important such programs can be in supporting the scientists of the future. “I do think that having had the BWF grant very early in my own scientific career made me more able to take risks, to have a dream project in the background along with day-to-day support,” she says. “The key aspect of the BWF Career Awards for Medical Scientists is that it’s for the person, not for a specific project. Psychologically, to get that message very early in your career—‘We’re investing in you because we think you’ll do something really worthwhile’—is a vote of confidence that can keep you going for a long time.”

By Sandra J. Ackerman, a freelance writer and editor based in Durham, North Carolina. The author of two books and more than 130 articles on science and medicine, she is a contributing editor at American Scientist Magazine and a member of the National Association of Science Writers.

Photos by Ed Newton. Ed is a freelance photographer based out of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He received his BA from Temple University in Media and Communications Studies with a focus on visual narrative. He placed 8th nationally in the Hearst Journalism Awards for multimedia team reporting for a piece on Philadelphia graffiti culture. He has spent his time documenting the city and developing specialization in the fields of documentary and lifestyle photography.