FOCUS In Sound #28: Dr. Robert Lefkowitz

Welcome to FOCUS In Sound, the podcast series from the FOCUS newsletter published by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. I’m your host, science writer Ernie Hood.

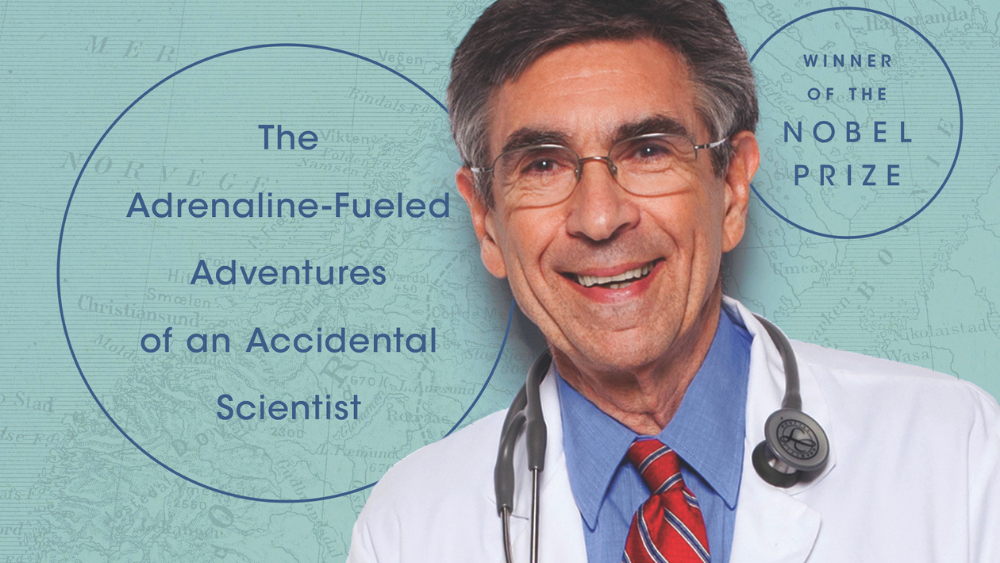

In this edition of FOCUS In Sound, we are honored to welcome to our microphones the winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Dr. Robert Lefkowitz of Duke University.

Dr. Lefkowitz is James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of Medicine, Professor of Biochemistry, Professor of Pathology, Professor of Chemistry, and Member of the Duke Cancer Institute. He has been at Duke since 1973.

He and his team pioneered the understanding of receptors, particularly G-protein coupled receptors, or GPCRs.

He has been a member of the board of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund since 2019. Most recently, he just published his memoir, titled “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm: The Adrenaline-Fueled Adventures of an Accidental Scientist.”

Bob Lefkowitz, welcome to Focus in Sound…

Thank you very much, Ernie, it’s a pleasure to be with you today.

Bob, your contributions to science and medicine are well-documented, so with your permission, I’d like to spend our time together in this setting on some other things, particularly your book, and your philosophical approaches to life and to a career in both research and clinical medicine.

It would be a pleasure to talk with you about those things today.

First of all, Bob, I have to tell you how much I enjoyed reading your book. It was warm, funny, and really communicated your warm personality, your love of science, your devotion to medicine, and your mischievous side. How did the book project come about?

Well, that’s an interesting story. As you know from reading the book, I’m a bit of a raconteur, and I love telling stories. I love telling stories, and anybody who’s worked with me or knows me knows that I love to tell stories. Sort of like your aging grandfather, when you hear the same ones over and over. But at least there are always new people to regale with my various stories. In any case, for, golly, a couple of decades now, people have been urging me to write some of these stories up. They keep saying, “Bob, why don’t you write a book? Why don’t you write a memoir? Tell the stories.” And I always could find reasons not to do it. And I strongly suspect I would not do it, But then, several years ago, one of my former trainees, one of my former post-doctoral fellows, a guy named Randy Hall, who had been with me in the 90s for a few years and is now a professor of pharmacology at Emory, was visiting me, because he, like me, is an ardent Duke basketball fan. And he comes up once every few years to watch a game with me. And over dinner, before the game, I was regaling him with stories, and he started in with the usual refrain, “Bob, why don’t you write these things up?” And I said, “Nah, I can’t do it, I’m too busy.” He said, “Look, I’ll make a deal with you.” He says, “Do you know the book Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!?” And I said, “Yes I do know that book. It’s a classic.” It was a book in which Nobel laureate Richard Feynman, also a raconteur, tells many of his interesting and quirky stories to a former trainee of his, a fellow named, I think, Ralph Leighton. And together they wrote them up. So Professor Hall says to me, “Bob, I’ll make a deal with you. How about you tell me your stories, I’ll write them up, I’ll record them, write them up, you can edit them, and we’ll put together a book.” And I said, “Let me think about it.” Which I did. But it seemed like too good an offer to refuse. So we started.

We spent about a year, pretty much all of 2019, basically doing it. The procedure was, we would talk by phone for an hour-and-a-half to two hours once a week. He’d record everything, write up the stories, he developed a nice narrative structure to put the stories into, which is basically the story of my life and career, and together we shaped the book. And we found ourselves an agent, a literary agent, and he found us a very nice publisher, Pegasus, and as they say, the rest is history.

The book was published just a month ago and seems to be off to a good start.

I particularly enjoyed learning about your love of listening to and telling stories…tell us about the importance of narrative in research and in clinical medicine…

I think people tend to think that clinical medicine and research are totally disparate enterprises, and in some senses they are, but they also have some things in common. And one of them is the importance of narrative. This was first brought home to me at one of the very earliest points in my clinical training in medical school at Columbia. So I was doing my very, very first clinical rotation as a third-year medical student. I guess that would have been like in the summer of ’64. Although I was a student at Columbia, I was doing that rotation at the Mt. Sinai Hospital on Fifth Avenue in New York City. And I had this wonderful attending physician, Mortimer Bader. It was the very first day of round with him, and there was a group of students and a couple of interns, and a case was being presented by one of the students. And after some discussion, Dr. Bader turned to me and said, “Mr. Lefkowitz, you’ve heard the case and the discussion.” And he said, “I’d like you to re-present the case with the following proviso: you may change none of the facts or data, but you’ve got to tell me a different story.” Well I was nonplussed, I said, “But the data are the story, how can I tell you a different story?” And he said, “Well, that’s what I want you to do.” I was flummoxed, I said, “I can’t do it.” So he went around the room, and nobody was willing to even try. He said, “Okay, just this once, I’m going to illustrate for you.” And he went ahead, without changing any of the facts of the story, and told a rather different narrative. He emphasized certain points that had been not emphasized in the initial presentation, and having brought the narrative out in such a different way, he arrived at a rather different diagnosis with a different prognosis and treatment. We were all very impressed. And over the course of the month that we spent together, he made us do that every day. And so we all learned in an clinical setting that data are data, but they’re not the story. The story is something you impose, through your own synthetic abilities and creativity, on the data.

Now at that point in my career, I never dreamed I would become a scientist, I had no desire to become a scientist. But years later I would learn in the laboratory that exactly the same thing was true. Data are data, they are not a story. So after we’ve been working on a project for a while, and feel that we have enough data to write a paper, we’ll generally sit down and we’ll have a number of figure panels, which will be the different panels of data that we want to show in the paper. And then we’ll start moving them around. You may want to take this figure and that one becomes the last figure. Alternatively, you could swap them out, and what was the last figure will be the first figure, that will be a totally different story, and little by little, we work out what is the best narrative to impose on these data. So it’s really very much the same exercise, and I really owe Dr. Bader the credit for first raising my sensitivities to the fact that a narrative is something that you shape data into, not necessarily the opposite.

You call yourself an “accidental scientist.” After your early career in clinical medicine, how did you serendipitously transition into research?

Well, you used exactly the correct word, Ernie, it was serendipity. I graduated medical school in 1966, and that was the height of the Vietnam War. At the time, there was conscription, there was a draft, a lottery draft, for all men over 18 years of age. And it was exactly that, it was a lottery. Everybody got a number, a draft number and a draft card, and they literally picked the numbers out of a big barrel. And if your number came up, you were drafted, and spent your, for the most part you were going to spend your time in Vietnam. And if your number didn’t come up, you were scot-free. For physicians, though, it was quite different. There was something called the Doctor Draft, and that meant that there was no lottery, everybody was drafted. And everybody was drafted upon graduation from medical school. Now, the way things worked was, you were drafted but you could sign up for something called the Berry Plan, where would get a further one- or two-year deferment to do an internship, or maybe an internship and a year of residency, and then you went in. You went in for two years, and you spent one year in Vietnam, almost for sure. And the branches of service that you could sign up for were Army, Navy, Air Force, and the United States Public Health Service. The United States Public Health Service, at the time, was considered one of the military branches. Hence, if you went in there as an officer, it fulfilled your draft obligation. However, it was by far the smallest number of slots compared to the other service branches, and it was extraordinarily competitive to get a commission in the Public Health Service. Why? Because many of their billets as they were called, many of their assignments, were in the continental United States, not in Vietnam. This included anything from working as a prison physician in the federal prison system to being assigned to research establishments such as the National Institutes of Health and the CDC communicable disease center in Atlanta. So everybody wanted that assignment, and it was extraordinarily competitive to get in there. So they were able to get the best and the brightest.

I was fortunate that I had high grades and good recommendations, and so I got that commission, as a lieutenant commander, they had naval ranks, in the Public Health Service, and was assigned to the NIH, where I spent the next two years. I was not at the NIH because I was dying to do research. I was there because I didn’t want to support a war which I viewed as immoral if not illegal. And that was the same for many of my colleagues there. In fact, to that point in my career, I had never thought about doing research. Not in high school, even though I went to the Bronx High School of Science, and not in college, and not in medical school had I ever done any elective work in research, and independent study in research. I loved science. I was a chemistry major. But I loved learning what other people had discovered. It never entered my mind that I would become a scientist myself. But here I was, and it beat the other alternatives. And so I went to work. And we spent about twenty percent of our time doing clinical work. I was actually assigned to a clinical endocrine service. And the other eighty percent we were assigned to a basic research laboratory. And there I finally began my very first efforts at research, guided by two mentors.

It did not go well. For the first year, more, maybe fifteen months, nothing I touched worked. And this was a completely new, and I must say devastating experience for me, because, to be honest with you, I had never failed in protracted way at anything I had ever tried to do in my life to that point in time. So I was pretty miserable. And then six months into the experience, my dad died suddenly, of a heart attack, his fourth, at the relatively tender age of 63. And so that first year was pretty miserable. The only thing that was clear to me was that I was not intended to be a scientist of any kind, and that as soon as my two years of draft obligation were up, I needed to get the heck out of there and get back to clinical medicine. And so I made arrangements that upon completion of my second year, I would go to the Massachusetts General Hospital, which is a Harvard teaching hospital in Boston, and finish my training in internal medicine and cardiology. As fate would have it, about 18 months into my stay there, my work started to get traction, and in the final six months, I made a lot of progress, made some significant advances, and published my very first few scientific papers. In fact, my mentors were so excited about the way the work was going that they did everything they could to persuade me to change my plans and stay on at the NIH and advance the work. But despite the successes I was far from convinced, and so I went off with my family, I had several small children by then, to Boston to find my future in clinical medicine. And so I threw myself into the clinical work at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and loved it. I had always loved clinical medicine, and that was something I had decided I wanted to do very early in my career, very early in my life, I should say. And I loved those first six months of very intense clinical work. But by the time I finished the first six months, I really began what for me was an epiphany, because I realized that I missed the laboratory. I missed the day-to-day challenge and excitement of trying to discover new things, rather than just doing what was the standard operating procedure for this disease or that disease, etc. And so, the ironic thing was that it was while being completely removed from a research environment that I finally realized I needed to be involved in research.

Now, I didn’t know what that meant at that point. I certainly never anticipated that I would be doing most of my time in a research laboratory. But I realized I did need to get back into the laboratory, at least for some of the time. And so I found myself another mentor, at the Mass General, and began working in his laboratory. And for the remaining two-and-a-half years that I was in Boston finishing my internal medicine residency and doing my cardiology fellowship, I also worked part of the time in the laboratory, and it was there that I began the studies that I would eventually pursue for my whole career. Once I move to Duke, which was in 1973, I initially spent, for the first couple of years, I probably spent about forty percent of my time doing clinical work on the wards and in the clinics, in medicine and cardiology, and about forty percent getting my lab program up and running. But very quickly, the lab program took off, and I began spending more and more time in the laboratory, so that within a few years I would say I was spending eighty percent of my time or more in the lab. So the question is, why accidental scientist, or serendipitous scientist? Well, the answer is the Vietnam War. If it were not for the Vietnam War, and the fact that I was drafted and didn’t want to go to Vietnam, but preferred to have a stateside assignment, no way I would have ever walked into a laboratory, and I think I would probably have spent my career very happily practicing medicine and cardiology, although to tell you the truth, I can’t imagine that it would have been as gratifying and fulfilling a career as the one that I’ve had.

Bob, one of the themes I wanted to ask you about is the role of the physician-scientist. Quoting from your book, you write “I cannot imagine a more rewarding career than being a physician-scientist and having the opportunity to help patients at the bedside while also making discoveries in the laboratory that lead to novel therapeutics.” Your own career certainly exemplifies that concept. Would you elaborate on that?

Yes. Both clinical medicine and doing scientific research are extraordinarily fulfilling careers. But I think they speak to different aspects of our personalities. When I speak to students about my career, I often title the talk, “A Tale of Two Callings.” Calling, of course, referring to some deep-seated, intuitive sense that you have a certain destiny. We tend to associate the term with clergy. But you can feel a calling to essentially any occupation or profession, and in my case, I really felt what in retrospect was a calling to the practice of medicine, to being a doctor, probably by the time I was eight years old. And that was motivated by my absolute admiration and awe of my family physician. That’s not an unusual story for why kids get interested in practicing medicine. They just are so impressed by their own family physician or pediatrician. On the other hand, as you heard, I also eventually felt a calling to scientific research. They speak to different aspects of ourselves. As a physician, people often say to me, well you know, you wound up spending the bulk of your career in the research lab rather than on a ward, and I’ll tell you it was 80-85% once the first few years were done, and I did that through my whole career. And for the last fifteen years, I’m 78 now, my last fifteen years I hung up my stethoscope altogether, despite the fact that you see me on the cover of my book with a stethoscope around my neck. I no longer wield it, although I think I can wield it fairly effectively. And as an aside, I just renewed my medical license, for reasons that are unclear since I no longer see patients. In fact, my wife is continuously asking me, “Why do you spend $250 a year to keep an active medical license and go to all the continuing medical education courses that you need to, when you no longer see patients?” And what I tell her is, because it’s just part of my identity at this point in time. And as I was saying, people often say to me, given that you spent the bulk of your career in the lab, do you regret the many years that you spent in medical school, in house staff training, in cardiology training, do you regret that? And I would tell them, no! For me, the greatest privilege of my life was to serve as a physician, to have the trust of patients who were at their most vulnerable, because they’re sick and sometimes dying. To be able on many occasions to bring comfort and some relief of suffering, and from time to time, to actually save a life. I said, I can’t imagine a greater privilege that one could have in this life than to have been in such a position.

On the other hand, I never viewed medicine as a particularly creative enterprise. And to the extent that I was feeling certain creative instincts, this just hard-to-define desire to want to do something new, go where nobody ever went before. No, I didn’t find that very basic need, at least for me, being fulfilled taking care of patients. And that’s what I drew from the laboratory. Now, the interesting, even ironic thing, is that there can be no doubt that I ultimately reached and touched the lives of so many more patients because of the research that I did, which now undergirds, they say, about a third of all FDA-approved drugs, than I ever could have touched by seeing patients. That was not the intent. I never set out to discover a new treatment or a new drug, I was just curious about a certain subject, these receptors for drugs and hormones, and I just wanted to understand. But of course that’s the wonder and the magic of fundamental biomedical research. That even though the research itself may not be directed at finding cures for diseases or new drugs, often in the fullness of time, others can pick up the research that you’ve done at a basic level and turn it into new treatments. We see that all the time. And this tends to happen, I think, more often with the research of physician-scientists, even when, as it is in my case, it’s very basic research, just because of the way physicians look at problems and the kinds of problems that interest physician-scientists. But alas, and at this stage of my life I’ve developed a real passion for trying to encourage and inspire young people to pursue careers as physician-scientists, because our ranks are being strikingly depleted. Recent studies have shown that only about 1-2% of all physicians identify themselves as doing any scientific research at all. And this is a big problem. And I think it’s never been brought home more than it is in these terrible days of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. We have to say to ourselves, who’s the next Tony Fauci? Where is the next Tony Fauci coming from? If we don’t replenish these ranks, we’re going to be in big trouble. And by the way, Tony Fauci is a very good personal friend of mine. In fact, we were, if I can use the term, classmates at the NIH. We went to the NIH at exactly the same time, 1968, and we’ve been good friends ever since. That program I was in at the NIH, would lead to a whole generation of physician-scientists, including people like myself, and Tony, and amazingly, between 1964 and 1972, the peak years of the Vietnam War, that program of the Public Health Service at the NIH, trained ten individuals who went on to win Nobel Prizes, and many, many hundreds who became professors of medicine, deans, all sorts of things. So it was a remarkable program, and the serendipity of it, which touched my life, also touched the lives of hundreds of other people who would eventually become physician-scientists.

Bob, another major theme in the book that I certainly wanted to explore with you is the profound value of mentorship. In fact, you devote a whole chapter to mentorship. Why is it so important?

This is an excellent question. If you look at scientists who are, shall we say, at the top of their game, the ones that win Nobel Prizes, the ones who are elected to National Academies of Sciences, and you ask the simple question, in whose lab did they train? Or in whose labs, because most of us had anywhere from one to three mentors. What you invariably find is that there’s quite a correlation between the level of achievement of the mentor and ultimate level of achievement of the mentee. So for example, I made sort of a scientific family tree a few years back of nine of the ten of us who I just mentioned who went on from doing our draft service at the NIH…and by the way, we were called, initially derisively, but then as sort of a mark of distinction, we were called Yellow Berets. And this was a parody of the Green Berets. The Green Berets, of course, were our most elite combat soldiers in wars like the Vietnam War. And yellow of course I guess meant to indicate cowardice, because we wound up over here. But it was actually based on that, there was a song, Ballad of the Green Berets, which came out in 1966 and reached the top of the pop charts. And then the very famous songwriter and performer named Pete Seeger, a folk singer, made a parody of that called The Ballad of the Yellow Berets, and that was where this term Yellow Berets came from. So, I made a family tree of the people who trained nine of the ten scientists who’d gone, the young men who had gone on to win the Nobel Prize. Nine, not ten, because the tenth one was this year, so I didn’t get to him. That was Harvey Alter.

For half of us, we trained with a Nobel laureate, and in my case, I did not, but in no case for any of the nine, in no case did you have to go back further than the scientific grandparent to find a Nobel laureate. And in many of these lineages, if you carried them back, they were studded with Nobel laureates, like six generations in a row. And I think the Nobel laureates is just the tip of the iceberg. What it indicates is that there are transferrable elements about how to do science. They’re subtle. They’re not things that you can necessarily write down in a book or an essay. Rather they’re things that you learn by sort of living in the laboratory with a mentor. I mean learning how to do science, and to a certain extent definitely clinical medicine, these are apprenticeship experiences. You live with somebody. You watch them over time, usually years. And you internalize their values. I mean for example, what’s a good problem to work on? I mean that’s the single most important decisions that any scientist ever makes is, “What’s my problem? What am I working on? What do I want to figure out?” And the moment you make that decision, whether you realize it or not, you’ve set the upper limit on what you could achieve, because if you’ve chosen something fairly trivial, it doesn’t matter how brilliantly successful you are in solving that problem, it’ll still be a trivial solution. So that’s an example. But how do you know what’s a good problem? Well, there are a lot of things that go into that. It’s got to be something which can be important if you solve it, but it’s got to be solvable. But usually the more important it is, the more difficult it is to solve. So you’ve got to figure out how that problem works and how far along the spectrum of risk you’re willing to go. And what’s a good decision? Well nobody can tell you how to make that decision, but somebody can sort of show you by sort of doing it themselves. Or you’re working on something and it just isn’t working, you’re not getting traction. How do you know when to push on, as opposed to giving up? Maybe the problem is just not right for you or anybody else to solve it right now. The old country-western tune, you’ve got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em. And there are many other such decisions that need to be made along the way. I mean, you’re working toward a certain goal, but then a result comes up that you didn’t expect, which could indicate a side direction which might be even more important than the direction you’re going. It could be a huge discovery being dropped in your lap. On the other hand, it could be a completely worthless distraction, a rabbit hole, and if you enter it, you’re going to waste the next six months and completely lose sight of the original. How do you know which it is? Again, nobody can tell you. But if you watch a truly accomplished scientist deal with problems like that, you can begin to acquire and internalize their values and their tastes. So this is the reason that mentoring is so important. Because it’s really the only way to sort of teach the really important things about how to do science. I always tell people, if something’s really important, you can’t look it up in a book. And I think that’s why mentoring is so important, because it’s all about transferring those values, as well as many other things—instilling confidence, empowering people, these kinds of things.

Last question for you today: As a relatively new member of the board of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, what has your experience been like with it?

It’s been really a remarkable experience. As you say, I’m kind of the new guy on the street, I’ve only been involved for about a year-and-a-half. So I’m still really learning the ropes. And they have such a diversity of programs I’m still coming to grips with all that they do. And the board itself is of remarkable quality. I love interacting with them, and I learn a lot at every meeting. Lou Muglia, the president, is just a phenomenon. He’s unlike anybody I’ve ever met. His level of energy and dedication to the enterprise is truly inspirational. Something that I share with Lou, and I think with many members of the board, is a dedication to producing physician-scientists. And if I hope to have any particular impact through my service on the board, it’s in working with Lou and other members of the board to continue to develop and advance programs specifically targeted at physician-scientist development. Now, the Fund already has such programs. I have a particular pet interest myself, which is in trying to attract medical students to a consideration of becoming physician-scientists, by encouraging them to take a year out of medical school and to work in a lab. We often call these “year-out programs.” I’m beginning to work with Lou and other members of the board to see how Burroughs Wellcome could support such efforts.

Dr. Bob Lefkowitz, it’s been great pleasure meeting and chatting with you. Congratulations on the book and of course on your legendary career! Thank you so much for speaking with us.

It’s been my pleasure, Ernie.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this edition of the FOCUS In Sound podcast. Until next time, this is Ernie Hood. Thanks for listening!

Comments are closed.